share this post on

Interested in how we approach our financial projects?

Read our case studies

Physical currency has been part of human existence for thousands of years, but its reign is now coming to an end. We are conducting an increasing number of transactions through mobile payments and credit cards—and all the while cash is disappearing. This immense change is accompanied by unprecedented economic shifts and technological innovation.

New fintech products are emerging every day. Neobanks are starting to look like formidable challengers. Following the path set by start-ups, big tech companies are trying to ride the wave, for example, Apple launching its own credit card. Incumbent players in the financial sector aren’t sitting idle either, experimenting with new digital business models and services.

We at Supercharge believe that innovation needs to be directed by human needs on both the societal and individual level. Technology is an enabler—or sometimes a constraint—but it only provides a means, without defining purposes. This begs the question: what is the driving force behind the countless new financial solutions, and do they, in fact, respond to users’ real needs?

Do we really know how people think about finances? What induces users to make their financial decisions?

Only by understanding the underlying mental models and psychological processes can we hope to answer these dilemmas.

If you work on digital or financial products (or would like to get better at your finances), follow our article series to dig into the complex psychological processes behind financial decisions. Understanding your users’ thinking can lead to a successful product strategy.

In this first article, we are going to discuss the mental accounting bias that influences us when we categorise our income and spending or associate various risks with specific investment goals. I will also mention some product feature ideas designed to turn this very phenomenon to your users’ advantage.

Many of us may be familiar with the feeling of getting an end-of-the-year-bonus. Being handed some extra cash is always a joyful experience, and by the time it pops up on your bank account you have probably made up a detailed plan on how to spend every cent of it. Buying yourself something big, definitely something expensive—sounds like the right thing to do, doesn’t it? You have always wanted that electric scooter, or is it the dream holiday in Mexico…?

But why do we like to spend our bonus differently than our monthly salary?

If we don’t buy that scooter from our regular hard-earned paycheck, why does it seem okay to do so from a bonus?

The story above is a perfect example of mental accounting: People handle their money differently depending on its source.

Mental accounting happens when we create special accounts or categories in our minds. We then classify our income or spending based on these.

A bonus is exactly the same kind of money as your monthly salary, so thinking rationally you should handle it the same way. Still, since you receive it on a special occasion, and—hopefully—your bonus is higher than your usual paycheck, you ‘book’ the two differently.

This is the moment when you create a new ‘bonus account’ in your head. By doing so, you inherently decide that its contents (your bonus money) will be treated in a special way: the rules of spending are going to be laxer here than on your ‘salary account’. This trick is how our mental booking deceives us.

Mental accounting is basically an umbrella term for multiple biases—irrational thinking patterns influenced by fundamental human instincts—that affect how we handle money. If you are interested in the mechanics at work (many of which are related to framing and loss aversion) we recommend “Thinking Fast and Slow” by Nobel laureate Daniel Kahneman.

Long story short: we handle different types of income according to different rules. Moreover, the same could be said about our spending habits. When we categorise our spending and divide it into separate virtual pockets—such as groceries, travel, nights out, etc.—the aforementioned mental accounting bias comes into play again.

But… this kind of budgeting method should be beneficial for our finances, right? Yes, and no.

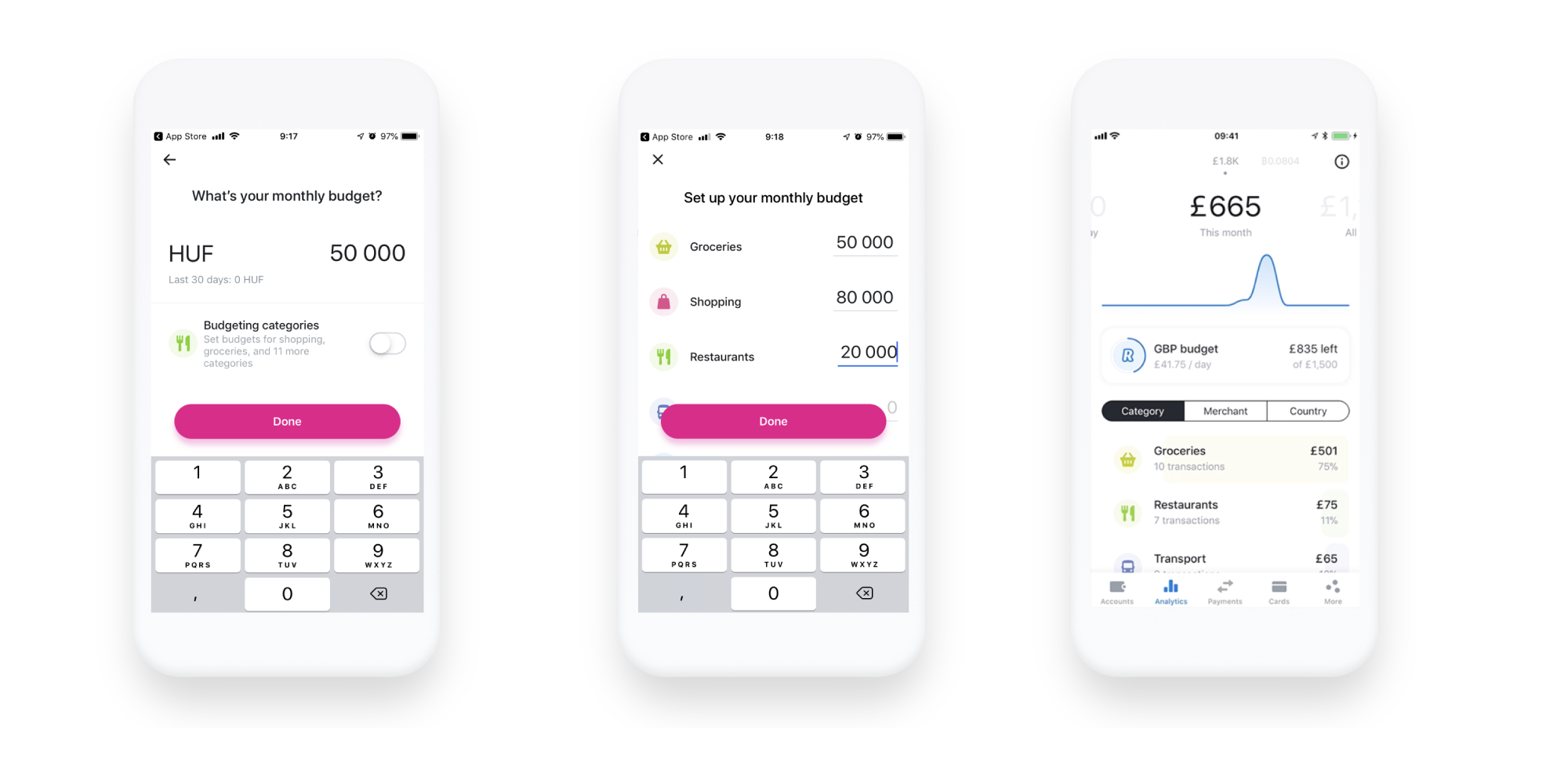

In recent years countless personal finance management apps (like Revolut or Mint) have released features to help users by classifying and automatically analysing their spending habits. Such categorisation promises us better navigation through the tricky waters of our finances.

For example, if you realise you have been spending too much on clothes, you can create a monthly budget for clothing items and thus limit your impulse shopping. In the end, you have effectively saved money by using your app’s categorisation and budgeting system.

However, this type of budgeting is a double-edged sword:

By mentally creating a separate ‘clothing’ budget that you can spend every month, you’ll be authorising yourself to buy a new pair of shoes even when you don’t need one.

You don’t have to be a shrewd tax advisor to pull some tricks to manipulate your numbers and fool… yourself. We all do it: when we go to a restaurant instead of cooking at home, suddenly the expense no longer goes into our ‘food’ budget, but is rather accounted for as ‘entertainment’ or ‘nights out’. By classifying our spending flexibly, we convince ourselves that the higher cost is justified.

If you remember one thing from this article, it should be this:

Humans are not fully rational when it comes to finances. Our decisions are rarely governed by basic arithmetics.

This realisation has shaken the foundations of classical economics once already, so you too have to be conscious of it when designing products in the financial domain.

The problem is obvious—but what product features could help users avoid the distorting effects of mental accounting?

As you can see, mental accounting is a natural behaviour which drives us when we handle money: building features based on this psychological model will result in an easy-to-use, intuitive product for everyone. But coming up with a solution on your own is almost never the right approach.

Conducting proper user research will, however, lead you to understand people’s behaviour, so you can design your product along the lines of your new insights.

Designing several financial applications in the last decade, we have conducted many user interviews about how people are trying to save money and categories in which they are keen to reduce their spending. The usual user journey is the following:

So it’s a great start if your product categorises spending automatically. But if you really want your users to take an actual step toward financial well-being, your product should combine categorisation with budgeting.

Each category needs a limit, a certain budget, and should inform the user when they have reached their average (or budgeted) spending within the category at hand.

Various savings solutions can also be integrated into this concept. When a user does not reach the budget in a category, the app could move the leftover sum to a savings account. This makes it easy to visualise how much they have put aside, which is a motivator.

We should try our best to remind our users that every (virtual or actual) dollar bill is interchangeable, no matter its origin or what you spend it on. The next product feature idea will effectively help users to remember this.

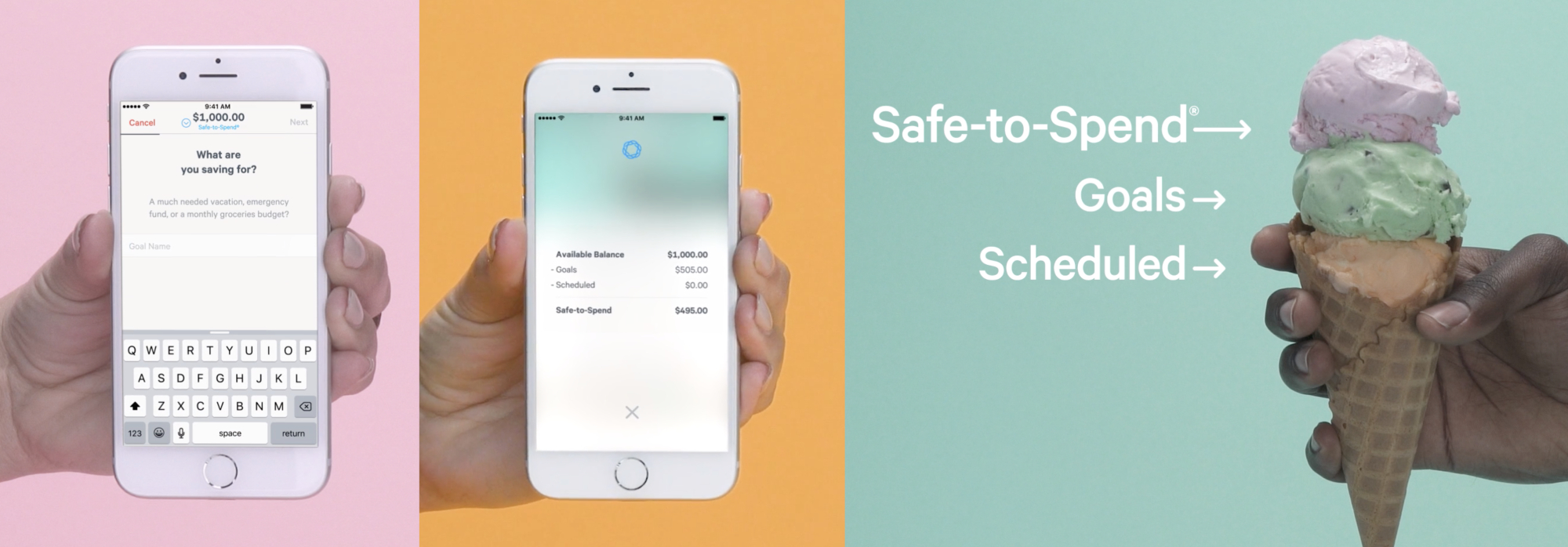

The neobank Simple has realised that categorisation may not be the best way to keep our spending under control. Instead, they focus on the concept of financial goals, i.e., what users want to achieve. You set up your financial targets and enter your fixed costs, such as ‘saving €100 a month for a new MacBook’ or ‘€400 for rent’, and the app simply does the math for you.

Simple takes your account balance, subtracts the amount you have earmarked for recurring bills and financial goals, and lets you know exactly how much money you have left to spend.

This system helps users to reach their savings goals while allowing them to spend on anything from the remaining ‘general’ budget.

Simple's idea can be boiled down to the conviction that every dollar you spend has the same value (thus negating the interference of mental accounting) while helping you save.

We already know that we tend to create different pockets for income and expenditure, but why not do the same for savings as well? The concept of goal-oriented savings also relies on mental accounting.

Researchers have realised that people find making monetary decisions easier when linking various financial targets to their life goals.

Saving money for a car or for an apartment is a lot more tangible than putting it aside for a distant, foggy future we can’t envision. In this case, specifying our exact objective and creating a ‘pocket’ for it ends up being an advantage. One dollar saved is still worth one dollar, but keeping up motivation is key for building up significant savings. By specifying and visualising the target, we simply end up saving more.

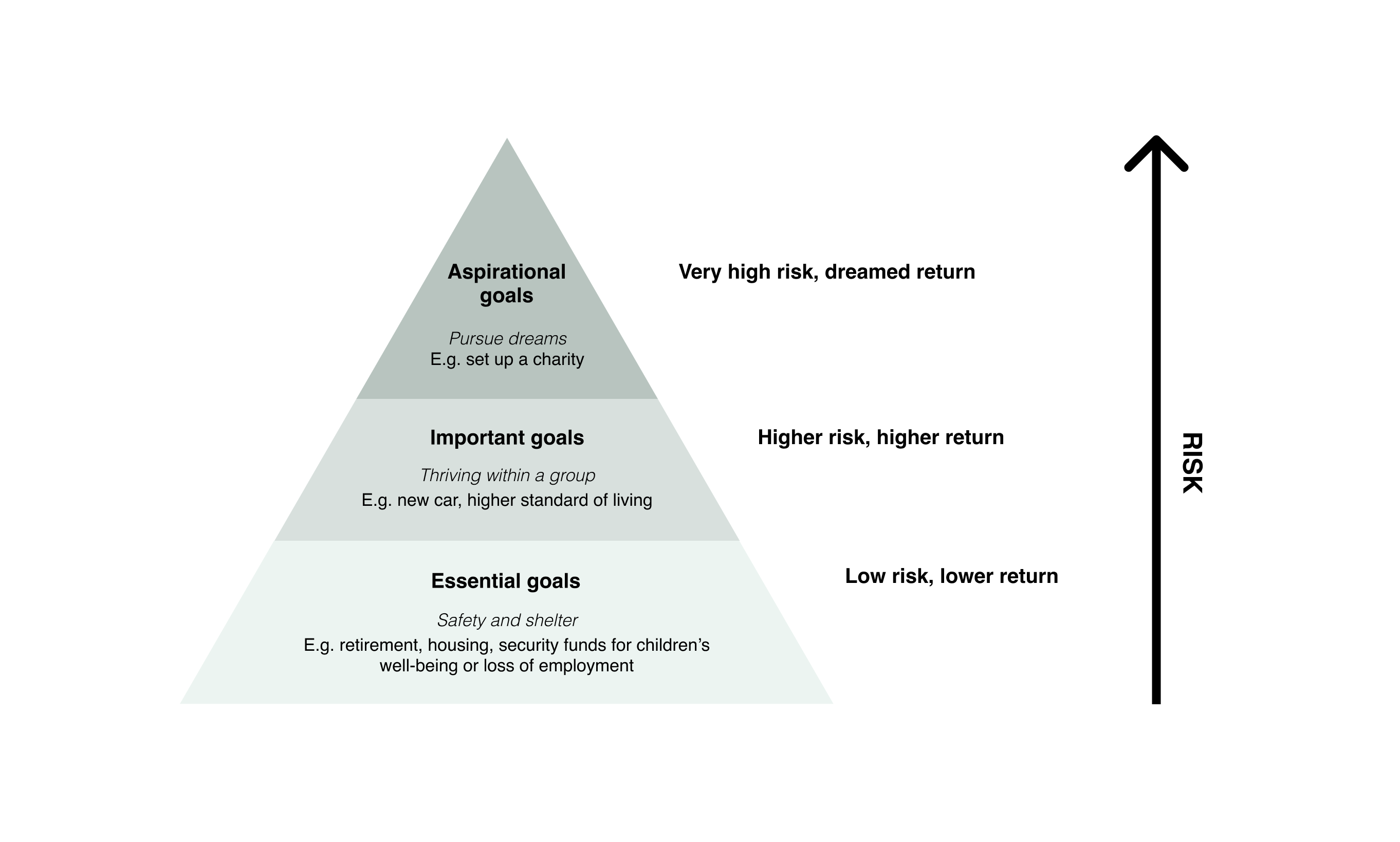

In the meantime, I need to highlight the importance of how we associate different risks with specific goals. With goals concerning our basic needs—such as housing or retirement savings—we usually like to play it safe and take fewer risks, accepting lower returns. On the contrary, when it comes to ‘dreams’ like buying a new car, we are ready to take greater risks with our investment for a greater possible reward. If both types of investments amount to the same sum, this behaviour hardly seems rational—but we are far from rational beings.

The following three feature ideas will help you create successful financial products harnessing the concept of goal-based investment.

Contrary to traditional investment portfolios, with goal-based savings, we can help users set up concrete financial plans that increase their willingness to save efficiently.

When users start specific goal-based savings or make an investment, they will imagine their new house and the colour of the paint they will choose for the picket fence. Unlike selling portfolios, ‘selling goals’ that invest in different portfolios are much more alluring – and leads to more effective sales. When buying securities from your bank, you probably aren’t thinking about the hardwood floors of your new apartment… but if you opt for goal-based securities, you might do just that!

In short, investing in a certain life goal is a much more tangible, easier-to-rationalise event than just saving money in general. While surely effective, goal-based savings can also provide a special and joyful user experience. (See our product concept below, for example.)

Research has shown that if we define a specific date for a particular future event, people will save more for it. When discussing long-term investments, instead of saying ‘in 10 years’ use exact dates if possible.

Motivating your users should be more successful if you estimate their date of reaching the financial goal at hand.

You could gather information with a few questions, then help people relate to their future self, e.g.: ‘How old are you?’ … ‘You’ll be 72 in 2037, probably retired.’ These additional features can help users visualise a more realistic and tangible future, making it easier to concentrate on their goals and objectives.

A product designer’s role is crucial when it comes to nudging users in the right direction and helping them make good decisions. This is especially true in the financial world: finding the optimal financial product is a challenging task, yet it can have a big impact on a users’ life. (For more on this read check out this research: Cass R. Sunstein and Richard H. Thaler, Nudge: Improving Decisions About Health, Wealth, and Happiness)

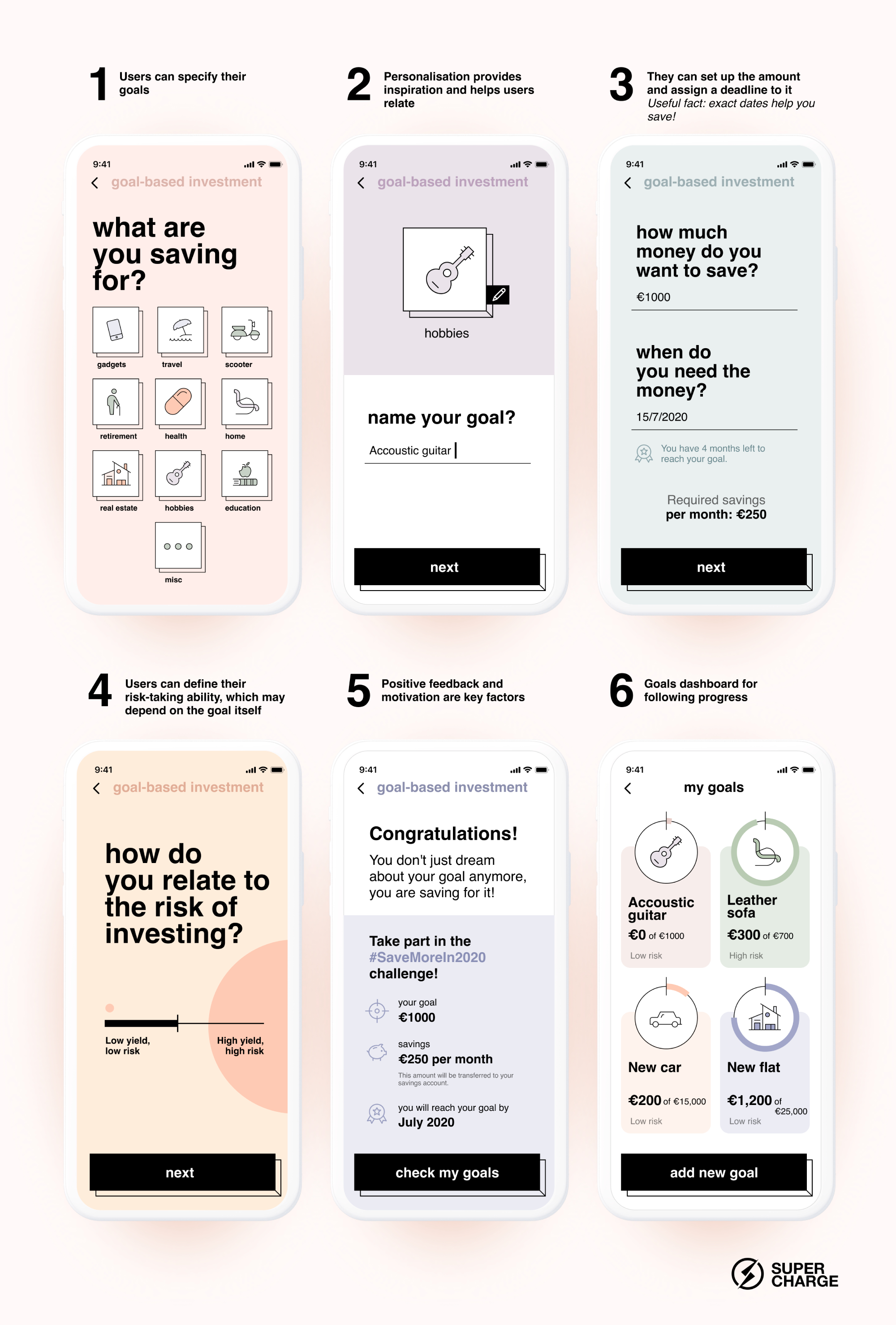

I created a basic goal-based investment flow, relying on the above-mentioned guidelines.

Users can set up various financial goals and assign deadlines to them (i.e., when they want to reach them), and the app will move their money to a savings account accordingly. They can also define their risk-taking willingness for each goal individually.

Understanding that mental accounting has a strong influence on our financial decisions and that it can drive us towards irrational financial choices is important for anyone creating products in the financial domain.

This knowledge helps us design effective countermeasures in our products and nudge users in the right direction, ultimately making a positive impact on their financial life. But even if our sights are set closer to home, being aware of these unconscious mechanics makes it easier to understand our own spending habits and to successfully save up for our dreams.